AED Success stories

AED in schools

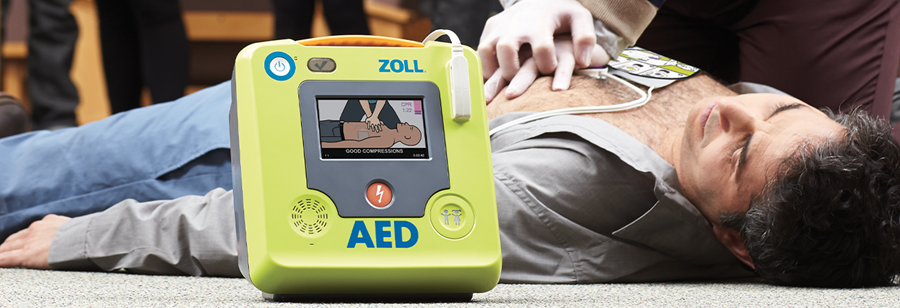

Philips HeartStart AEDs are designed to pull the stressed lay responder through

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) is the leading cause of sudden death in young athletes accounting for approximately 75% of cases. Not only was Philips was the first company to introduce a pediatric

defibrillation capability, but it also released the patent so that all AEDs could protect children. It was one of the best decisions Philips ever made. Choose HeartStart - it may be your best decision too.

K-12 Education

School-aged children are not immune to cardiac arrest. In fact, an estimated 5,000-7,000 children die from SCA each year, often on school grounds or playing fields, where contact sports injuries can increase the odds of an SCA event. That's why many schools, including districts in some of the largest cities like Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York City have installed HeartStart AEDs.

Seventeen year old Lindsay Hayden collapsed during class and went into sudden cardiac arrest (SCA).

Learn more about the generosity of one family and some quick thinking actions which helped save her life.Higher Education

Defibrillators treat sudden cardiac arrest, which can unexpectedly strike anyone, even on college campuses. AEDs do not just protect the student athletes at colleges and universities but anyone on campus who may suffer SCA. A recent study of SCA events at NCAA Division I schools found that older nonstudents such as spectators, coaches and officials accounted for 77% of SCA cases at sporting venues.

When SCA strikes, time is of the essence - be prepared with HeartStart defibrillators. Philips is the trusted leader with thousands of AEDs deployed on campuses across the U.S., and the official supplier for the National Athletic Trainers' Association. Choosing HeartStart may be the best decision you ever make.